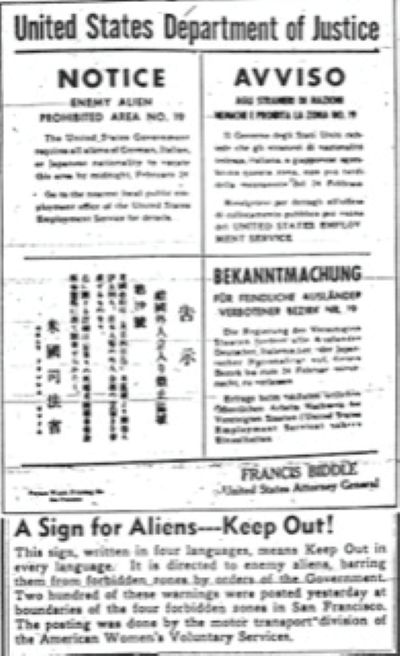

While researching my first novel, The Last Letter from Sicily, I stumbled on the book Una Storia Segreta by Lawrence DiStasi, from which I learned about government restrictions and actions during World War II that targeted some 600,000 Italians, so-called enemy aliens who were not yet American citizens. Many were placed under curfew, and some were banned from their workplaces. But what I found most jarring was the fact that about 10,000 Italian people were evacuated from their homes in California alone, and hundreds of Italian men were rounded up nationwide and placed in internment camps.

Those stark statistics inspired my second novel, Beneath the Sicilian Stars. I fell down a research rabbit hole, where I discovered the documentary film Potentially Dangerous, produced by Noah Readhead, Zach Baliva, and Naomi Baliva, which sheds light on this hidden history through interviews with historians and individuals with families directly affected by evacuation and internment experiences.

I spoke with Zach, who also served as the director, about the film. He shared how the documentary started with an entry to the Russo Brothers Italian American Film Forum, an annual fellowship opportunity sponsored by The Italian Sons and Daughters of America, AGBO, and The National Italian American Foundation, which supports projects that tell original Italian American stories.

The film would win the 2021 award, among other prizes and distinctions. And actor John Turturro signed on as executive producer. You can catch Potentially Dangerous on PBS. (Check your local listings for PBS member stations.) It's also available on DVD and streaming.

What inspired the making of Potentially Dangerous?

I learned about the Russo Brothers Italian American Film Forum shortly before the deadline in 2020. I wanted to enter something because I've worked mainly in narrative filmmaking, but I've also worked as a journalist and a freelance writer. So, documentary is kind of a natural space for that combination. The problem was I didn't have a topic, and the deadline for the film forum was approaching. I thought, "I'll fill out an application, and through the process, I'll get to know the people involved. They'll reject my application this year, but next year, I'll be prepared."

I needed a story, so I Googled "unknown Italian American story" or something. When you do that, the first search results are Larry DiStasi's work on this topic because one of his books (Una Storia Segreta) translates to an unknown story or a secret history.

I went through dual citizenship, and my family is Italian American. I had never heard of any of this before. And so, really quickly, I got interested in it.

Oftentimes, you find a story, and it's already been done, or there's already a novel, or there's already a documentary, or whatever. So, usually, when I contact people, they're like, "Oh, somebody tried to do this already, and it didn't work." And with this, it was the opposite.

When I contacted Larry, he said, "This has been my life's work, and I would kill for somebody to make a documentary about this. Please do; I'll turn over all my research and connect you with all the people."

I would have had nothing if Larry had not been involved or receptive or hadn't primed the pump by doing all his research. But I just contacted him at the right time. And so he was very, very receptive.

As I was going through the research with him, I started to realize this was something I had to be involved in. And primarily when I realized that there were people detained and held within Ellis Island, that was kind of the clincher for me because I remember going to New York as a young child, and you hear, "This is where our family came through." And just to realize that not many years later, these same people who saw this as a beacon of hope and freedom were held against their will in the same facility, to me was just this fascinating juxtaposition.

As I started doing more work, people were super receptive to being involved, and it took on a life of its own. We ended up winning the Russo Brothers Italian American Film Forum and got funded.

It was just being in the right place at the right time. And lots of credit to Larry, who is really the champion of this cause. And if it wasn't for him doing a lot of the work over the years… He put people in a position where they were more receptive to speaking to me.

I know that when he first started interviewing people, many didn't want to participate. And so 15 years later, when I came along, they were like, "Alright, we've started to tell this story, and now we want to see how far we can take it."

Zach interviewed several individuals about their family's experiences during World War II.

How did you approach the sensitivities of the story?

Larry had done a lot of hard work on that, but it was a weird combination of dynamics. I had to move quickly because we had a deadline. And if you didn't hit that deadline, which was five months during COVID with an $8,000 grant, you had to pay that money back. So I was moving very quickly, but one of the most important things to do was to build trust and get to know these people, so they want to tell you these very traumatic things that happened to them 80 years ago. You can't just fly in there and say, "Alright, the camera's on. Talk."

There was one very elderly woman whom I spoke to first. She was, I think, in her upper nineties, and she's the only person who refused to participate. She said she didn't want to appear on camera because she was insecure about her appearance. That was a little bit of an excuse. She had this really compelling story. I think she lived in a house near Pittsburg, California, with all these other people and was the one to help teach them English.

I worked with her two or three different times to try to convince her, saying, "We won't even put you on camera; it'll just be audio-only for research purposes." She was the only person who wouldn't do it, and it was very discouraging because she was the first person I approached, and I feared her reaction might be a sign of what was to come.

For everyone else, it was just moving as slowly as we could to make sure they were comfortable. And then it was also word of mouth. That helped because when I contacted people, I would say, "So-and-so sent me to you," or "Your cousin told me that you had an amazing story, and it would be sad if we missed it."

A lot of the work that I do as a journalist is interview-based, so I've done, in my freelance career, two or three thousand interview-based articles. You develop this natural ability to sit with people and learn how to make them feel comfortable and how to elicit the best responses. I didn't just set up the camera and right away say, "So what was it like when your father was ripped from your home?"

A lot of these people are elderly and have kids and grandkids who are a little protective of them, so there were some small hurdles, but overall, most people really wanted to get the story out there, especially because they realized—not to be morbid—this is their last chance.

Still from Potentially Dangerous, dramatizing an FBI raid of an Italian family's home.

Why do you think this aspect of history has remained hidden?

I think part of it is that they were so ashamed, but also afraid of speaking out. We featured Tony Rosati from the other Pittsburgh, whose father was detained twice. He shared that his mother was paranoid for the rest of her life. For decades later, every time the phone rang, she would worry about who was on the other end, like, "Are they listening to our conversations? Can I trust law enforcement?"

When you think of all those dynamics, you realize these are the reasons why this story hasn't been told. These people are so reluctant to tell their stories because they're worried about what might happen to them and that something like this could happen again.

Your executive producer is John Turturro. How did that come to be?

My main goal with the project after it was done was to just get it to the widest possible audience. In the world of film, especially today when it comes to distribution, it's sort of like a used car salesman or loan shark world where everybody wants a piece of the money, and everybody gets it except for the person who creates the content. So you get all these offers from people. But unless you are a really big name, usually what happens is you get a very little amount of money. They put it on the shelf, and it'll be available for five bucks on iTunes or whatever, but nobody's really going to rent it because there's no marketing or whatever.

The trade-off for me was that if we could get it to public television, there might still be little money involved, but millions of people would see it. That quickly became the goal, and then I realized I would have a greater chance of reaching that goal if somebody like John was involved.

John comes from a military family. His family is from the parts of Italy from which several of the story's families came. And I had seen that he had worked with some notable Italian directors, and I just felt like, "OK. Out of all the people I could approach, he has to be at the top of the list." And he was super receptive. He said, "I'm really busy, but anything I can do, even if it's just lending my name to this project, anything I can do to help, I would love to."

Without him, I don't think we would've gotten to PBS, for example. He really helped us open those doors.

What other projects do you have in the pipeline?

Funding is always the wild card, and it's heartbreaking to me because, even within the Italian community, there are many causes and initiatives that these organizations already support. They all want to screen Potentially Dangerous, but there's no money to fund another project.

I was working on one for a while that ended up going away. It was going to be called The Last Goldbeater in Venice. I found this guy who's like 75 years old, and he's literally the last artisan in Europe who makes gold foil and gold leaf by hand.

Every day of his life for the last 50 years, he's gone into this closet-sized studio and beat a bar of gold—I forget the exact number—like 30,000 times with a 13-pound hammer to make one leaf of gold foil. They use this on the most important monuments in the world, and if they use machine-made materials, it's not the same as all this stuff.

So the story was that if he doesn't find an apprentice by the time he retires, this very important cultural art form will go extinct, like mask-making, glass blowing, lace, and other Italian traditions. It mirrors the plight of the city of Venice, which is over-tourism and climate change.

We had a major hospitality brand on board to fund half of the budget, and then, at the last minute, they withdrew their support because they had other priorities for their marketing dollars in 2024. I couldn't ever replace them. Then the guy retired, and the story went away. In the documentary space, this happens a lot.

Now, I have another story. I found a group of West African refugees who have all fled terrorism and war and ended up in Italy, and they've formed a soccer team to sort of assimilate and give them hope and purpose as they rebuild their lives in this new country.

The cool part about it is that the Italian government sponsors them as an anti-racism movement. They placed them in the lowest tier of the official Italian soccer league, and against all odds (as this underdog story), they won the Cup in their first year and moved up from the ninth to the eighth level of the Italian soccer league.

One of their players signed a contract with a Serie-A team and scored a game-winning goal in his first game, and it kind of put them on the map. And so now, a lot of Italians know that this team exists.

Unless we find a sports brand, team, or somebody to co-fund this with us and produce it, then I'm afraid the same thing will happen. But that's the project now: to figure out if there's a way to fund this story before it also goes away.

There are lots of stories to tell, but limited time, resources, and money to do it. And for me, it's heartbreaking when a story that one really believes in just vanishes because of money.

Hundreds of Italian "enemy aliens" were imprisoned in internment camps across the nation.

How do you hope Potentially Dangerous will contribute to a greater understanding of Italian American history?

It's something I think about a lot, and not everyone agrees with me. I really do believe that because these events happened, they stopped publishing Italian-language newspapers in some places, and people started hiding that part of their personalities and that part of their identities. And that sort of contributed to my own experience in the Midwest of how my family is like, "OK. We're Italian, we're Italian American." But it doesn't really mean a whole lot to us, unfortunately. And these events had a big role to play in that. My argument is that because of what happened, we've been left with this caricature of what it means to be an Italian or an Italian American.

We have the mafia stereotype, and we have this very shallow understanding of the Italian American expression in the United States. My argument is that if this hadn't happened, there would be a more robust and deep expression of Italian Americanism because they wouldn't have had to hide certain parts of their culture to be accepted. Therefore, that expression would've been fuller and more complete for generations. And now you have all these organizations like the Italian American Future Leaders of America, and people of my age and younger who are trying to recapture that. But these events really played a part in that.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!