From a young age, Brooklynite Paige Lipari yearned for a space where she could bring together her passions for food, books, and the arts. As she grew older, she realized she also wanted to share what she loved with her community.

Following a trip to her family's home in Alcamo, Sicily, Paige decided that the space would be a bookstore catering to gourmands by selling Sicilian and Italian specialty goods alongside cookbooks and serving as an event space for foodies and neighbors in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. And so began Archestratus Books + Foods in 2015.

I recently sat down with Paige, who shared more about Archestratus's start, her deep connection to Sicily, the challenges and rewards of running a niche business, how she has engaged the community, and more.

Tell us about your connection to Sicily.

I'm Sicilian on both sides. My father was born in Sicily, and my mother is second-generation American. I have a very strong connection with my Sicilian heritage. We go to Sicily every few years and visit my family in Alcamo.

My family has a city house and a country house because it was four hours to Trapani by donkey, but now it's seven minutes. They're in the city house in the winter, and then they go to the country house for the warmer months, where they have vineyards. They grow grapes, and they sell mosto to winemakers.

I actually didn't go to Sicily until I was 19, which felt very late. And then we started going more and more, but my nonna always brought the Old World Italian. I never really related to this sort of gold chain/ white shirt Italian American—that just wasn't in my family. I grew up with a nonna who always had some wine on the table with some fruit and cheese. We always ate raw fennel after every meal.

She was very much into agriculture and would grow things all year long. The food was unique compared to other Italian American restaurants we visited. And she was my first anchor in that culture.

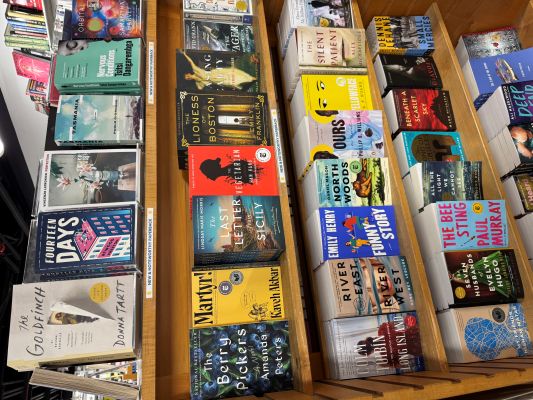

Archestratus specializes in vintage and new cookbooks.

What inspired you to open Archestratus, and what led to the naming of the bookstore?

When I was really young, I loved books, and there was this closet where I would sit and read by myself. And I was a latchkey kid with two working parents, so I started cooking for myself really early.

I kind of knew in the back of my mind that I wanted a bookstore. I also love design and making spaces feel warm and cozy. And then I love the arts, so the idea of having people perform in this space, doing conversations and talks, and keeping that intellectual stimulation.

It wasn't until I went to Sicily for the first time, when I was 19, and met my family, that I completely broke open this obsession with Sicilian food and, of course, Sicilian cookbooks. I fell in love with them, and it changed my life.

When I came back, it was kind of my way of connecting with them and also preserving my heritage because my nonna was starting to have dementia. The recipes were all in her head.

When I learned about Sicilian cuisine, my creative juices just flowed so hard in that direction. I could never really put my finger on why it was different or what it was about until I went there.

Sicily's so beautiful and unique, and it's amazing to me that now it's getting its flowers as far as how it is its own place. But 20 years ago, when I started out making this food and getting really passionate about it, nobody knew. No one was talking about how it's influenced by Spain and North Africa, and there are a lot of Middle Eastern flavors, and there's the Couscous Festival and all that stuff.

I was passionate about spreading the word.

Where did the name Archestratus come from?

I read Pomp and Sustenance by Mary Taylor Simeti and read about Archestratus, and I immediately felt a connection with him. He was kind of wild in what he wrote, and he was deeply mysterious; we don't know much about him.

I named the store first, and then all these answers revealed themselves later. He was a poet who was more interested in places and simplicity, enjoying himself and having a good time. Food was all about that and gathering.

Cookbooks are documents of places, times, and people. I'm interested in how food is a way of seeing the world and bringing people together.

How do you select the books for your collection, and do you have any personal favorites?

I go to book sales. I love books where it feels like there's a real voice. I know there's a place for more prescriptive things that fill a niche. I just make sure that they're really of good quality and were done with intention.

Some of my favorite books are Pomp and Sustenance and Honey from a Weed by Patience Gray.

Patience Gray's husband was a sculptor, and they would travel around the Greek and Italian islands in the Mediterranean, chasing marble for him. So she would spend time in these places. While he was doing the work, she would go out and sniff the windows of the homes, figure out what the women were making, and write about them in a strange, esoteric, funny way.

Can you share some highlights of the community spirit at your bookstore?

We started the Archestratus Cookbook Club in 2015, and it has always been successful. We pick a book every month, and then everyone shows up with one portion of a dish. Then we all just have this feast, take a little bit of everything, and try other dishes from the book to see if you want to buy it.

Our bake sales are probably the most incredible. We held a bake sale for the L.A. fires and raised $9,000 in three hours, which was matched by a corporate sponsor. We also held a bake sale for Joe Biden, one for Planned Parenthood, one for Ukraine, and one for Palestine.

We usually have around 80 bakers, and then it gets people to come. It's such a great model. You spend $20, but then if it's a big sale, that $20 can turn into $200.

What's been your biggest business challenge?

The pandemic was a challenge, but it wasn't my biggest challenge. In a bizarre way, I almost felt like I was ready. I already wanted to expand and had been researching more food vendors.

During the pandemic, we were a bookstore cafe, and I was already starting to think we were outgrowing this space. So, I was already researching vendors for fresh milk and eggs and trying different things. And so I had set up all these connections, and then the pandemic hit, and I was like, well, I could do a grocery pickup.

On March 19, 2020, we did a grocery pickup, which was one of the first weekends. By April, we had one day when we had to pick up for 220 people. They would come up on the street with their order, and then I would fulfill it. So I had this bizarre flow happen with the pandemic, and we were O.K.

My biggest challenge after the pandemic was when we expanded, and then I realized, "I don't like this. I don't want to do this. I don't like having a bigger staff, and I don't like dealing with this landlord."

I thought I would love it, that this was what we needed. But then I realized we needed to be smaller, more flexible, and lighter on our feet.

I did this big thing, saying, "We're doing this." Then, I had to pull back and make that hard decision to contract.

Every decision I make is pretty public, but I was not doing the thing that I know I love. I love making food, and I love cooking, but it was not making me happy anymore at that level. Facing that and just financially getting through that and out of it has been extremely challenging, and I'm still dealing with the effects.

What are your upcoming plans?

I know that people want recipes, and I want to share them. And so, figuring that out is going to be 2025, and starting to do that. I know there will be a newsletter, so I'm going to start writing one and sharing some of these recipes.

Another more community-driven thing I want to do this year is create a community zine and start making a cookbook with everybody, especially coming out of these bake sales. We have such a network of people who love to develop recipes, cook, and have family recipes. We started doing that before the pandemic, but it never got off the ground. And this is the year I want to make time.

What do you hope people take away from a visit to Archestratus?

I hope that they get inspired to be more of themselves. I hope that they see that we're operating on a frequency of not giving a shit, and I hope that they go off and they do whatever they want to do.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!