December 7 is a date which will live in infamy. It was the day Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, but that night, the Federal Bureau of Investigation also began arresting "potentially dangerous" Japanese, Germans, and Italians. And they did so before the United States was officially at war.

This response was far from last-minute. Since 1939, the FBI had been compiling lists of suspicious and allegedly subversive persons they decided required surveillance and, in the event of war, internment. Among the hundreds targeted and later interned were journalists, Italian Consulate employees, and veterans of World War I (when Italy and America were allies). Opera star Ezio Pinzo was arrested for allegedly altering his singing tempo to send coded messages to Benito Mussolini.

Internees were sent to military camps in states including Montana, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Maryland, and Texas, where many spent years imprisoned. How could the government do this? Title 50 of the U.S. Code, based on the 1798 Alien & Sedition Acts, gave them the power to detain "enemy aliens" in emergencies.

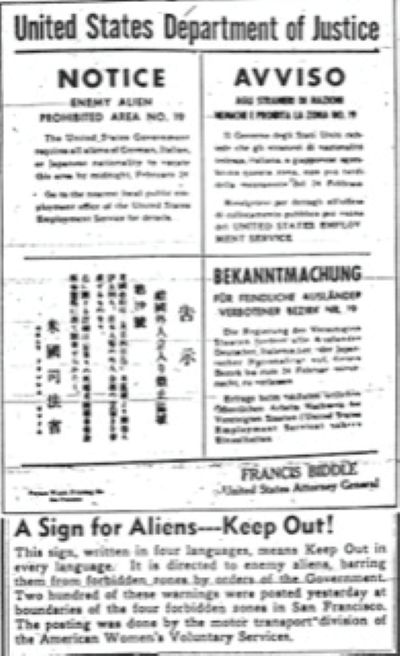

The government effectively declared war on much of its immigrant population, imposing restrictions on about 600,000 Italian residents without U.S. citizenship who, on Dec. 8, had been designated enemy aliens by presidential proclamation. These "enemy aliens" were required to re-register as such; FBI agents raided homes and confiscated weapons, radios, cameras, and even flashlights. Non-citizens on the West Coast were placed under a strict curfew, required to carry "alien enemy" ID booklets, and told they would need a permit to travel more than five miles. Those who did not comply were subject to arrest and detention.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the military to designate areas of vulnerability and relocate individuals deemed a threat to national security. More than 120,000 Japanese people, including American citizens, were forcibly displaced. What's lesser-known: By the month's end, the government ordered the evacuation of at least 10,000 Italian Americans from their homes in California alone. People had just days to relocate.

Why isn't this in most history books? The question bothered San Francisco Bay Area historian and author Lawrence DiStasi, whose father came to the U.S. from Italy. He began digging through records and archives, collecting testimonials, and eventually created a traveling exhibition called Una Storia Segreta, Italian for secret story and hidden history.

His efforts and compiled testimonies induced President Bill Clinton to pass the "Wartime Violations of Italian American Civil Liberties Act," which was signed into Public Law 106-451 in November 2000. While no reparations were distributed, the act acknowledged injustices suffered by Italian Americans during the war.

DiStasi compiled a collection of essays and accounts about Italian wartime restrictions and internment in Una Storia Segreta in 2001. He wrote a deeper analysis in Branded: How Italian Immigrants Became 'Enemies,' published in 2016.

I discovered these works in June 2020 while researching my World War II-era historical novels. Later, I encountered the original Una Storia Segreta exhibit at the Pittsburg Historical Museum in Pittsburg, California, where the federal government evacuated about a third of the population in 1942. The website, unastoriasegreta.com, reproduces the exhibit.

I was delighted to have the chance to speak with DeStasi about his important work and its legacy.

Share the story behind Una Storia Segreta with us.

I had never heard a thing about these events when I was growing up in Connecticut. When I came to California in the late 1960s, I started to hear about this real turmoil in the Italian American community, specifically in San Francisco and Pittsburg, up on the Delta. I thought this was really an important story, but everybody said no one would talk about it because they were embarrassed and ashamed. There was also animosity in the community because some people had informed on others.

Eventually, we in the American-Italian Historical Association's Western Chapter decided to hold a conference in 1993 at the University of San Francisco. And it was a sensation. Somebody at that conference said, "Why not do an exhibit?"

We had never done an exhibit before, but four of us decided that we could, in fact, do this. So, with Rose Scherini as our chief researcher, and I as the project director, and with Adele Negro then president of the AIHA Western Chapter, and a designer we found named Elahe Shahideh, who had done a previous exhibit at the Museo Americano in San Francisco, we set out to make it happen. We had panels nailed to the wall, and we managed to gather some artifacts. A friend of ours, an Italian teacher, suggested the title Una Storia Segreta, which means both "a secret story" and "a secret history."

Opening night was an absolute smash sensation. People from all over the Bay Area wept in front of the panels. We got more publicity for that than any other effort we had ever made. It was featured on the front page of the Style section of the San Francisco Chronicle.

That started us off, and Bill Cerruti from Sacramento, with the help of Connie Ilacqua Foran, whose father had been interned and whose husband was a senator, got approval for the exhibit to come to the Capitol in Sacramento, and that was huge. The governor signed a proclamation. We had a banner in front of the Capitol that said "Italian American Exhibit." Bill spent about seven thousand dollars to make our panels, which were displayed around the rotunda of the Capitol.

It was a beautiful exhibit, and that gave us more publicity. We started getting requests from all over California from Italian-American organizations who wanted to host the exhibit. When it went down to Monterey, where many fishermen were affected, our friend Hugo Bianchini, an architect, decided to make frames for each panel. We got the exhibit framed and put it in two traveling crates.

Hugo said, "This exhibit will be traveling for five years." We thought he was crazy. It turns out that Una Storia Segreta ended up traveling for more than twenty years.

Una Storia Segreta panels on display at the Rayburn House Office Building

How did the exhibit inspire the passage of legislation?

People would request that I come with the exhibit to give a talk, so I went all around the country. We had it at several state houses as well, all without soliciting any organizations. It just traveled by word of mouth.

The highlight was when we displayed it in the Rayburn House Office Building in Washington, D.C. John Calvelli, the chief of staff to Elliot Engel at that time, saw the exhibit in the Rayburn and said, "We can pass legislation about this." So, he took the lead in getting the legislation drawn up and got us Judiciary Committee hearings, at which I and several community leaders spoke. We managed to get Ezio Pinza's wife to come and testify at our hearings. She gave a very moving testimony. We also persuaded baseball great Dom DiMaggio to testify.

We also had several people from the Bay Area testify in Washington, D.C. Afterward, John Calvelli said, "We hit a home run. We're going to get this legislation passed."

After two tries, the Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act was passed and signed into law by President Clinton in 2000. That was a real success.

Attending Judiciary Committee hearings in Washington, D.C.

Was your own Italian family affected by these wartime events?

I would go around the country saying, "Can you imagine there are people whose own families were affected and didn't even know about it?"

Well, I turned out to be one of those people. Because my father and my uncle were both classified "enemy aliens" during the war, and nobody ever talked about it until our exhibit went back east.

My sister asked my cousin, "Did you know about any of this? Can you imagine?" And my cousin Rosemary said, "Well, yes, my father was an 'enemy alien.' They came and took our radio."

Then my daughter was looking into Italian citizenship, and I asked a friend in Washington if she could send me my father's records. That's when I learned that my father was actually an "enemy alien" himself. He never said a word about it. We have none of his papers or anything like that, but that was the story. That just knocked me off my feet; I couldn't believe that that was the case, but that was why we called it Una Storia Segreta. Secret story, secret history.

A young Costanza Ilacqua Foran stands between her parents.

Which stories featured in Una Storia Segreta and Branded stand out most?

Connie Ilacqua Foran's father in San Francisco was interned. They interned him because he worked with the Italian Consulate a little bit.

Rose Scudero became one of our star informants because her family was evacuated and had to move out of Pittsburg. Her father could stay, but she left Pittsburg with her mother. When the restrictions were lifted, she said she was a little bit like Paul Revere, running back to Pittsburg through the streets, shouting, "You can go home now; you can go home now!" That was really moving.

Notice to evacuate from U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle

What message or lesson do you hope to share with your work?

During wartime, anything can be justified. You never know what the powers that be can make the case for.

I just want readers to know that this happened despite all the denials and attempts to hide it. History is never quite complete, and you can always find out something new.

I'm very proud of the work we did. We put this thing on the map, and it'll never again be forgotten or hidden because over 600,000 Italian Americans were affected by this one event. It's one of the biggest things that's ever happened in the Italian American community.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!