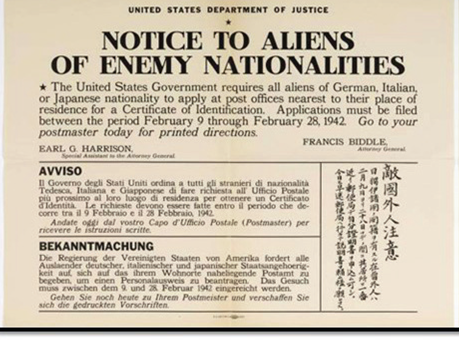

The first week of December 1941 brought fear and uncertainty for Italian immigrants in the United States. Nearly 600,000 were labeled "enemy aliens," kicking off a period of restrictions: forced registration, curfews, home searches, travel bans, and even internment. While Beneath the Sicilian Stars portrays one family's struggle in California, fishermen on the East Coast faced similarly devastating disruptions, many of which remain untold.

Maria "Mia" Millefoglie discovered this darker chapter of American World War II history while delving into family history for her manuscript, and as a contributing author to Our People Our Stories, a collection of over 80 stories, poems, vignettes, and photos celebrating Gloucester, Massachusetts' history and the resilient individuals who call Gloucester home.

Mia's mother had recounted life in war-town Sicily, the bombs, the poverty, and how she was forced to beg for bread. Her grandfathers were banned from fishing commercially on Gloucester's shores and could no longer send money back to their families. Other relatives recounted stories of families selling mattresses and jewelry for food. These stories prompted Mia to understand why.

That quest for knowledge led her down what she calls a rabbit hole, eventually culminating in Branded: Enemy Aliens in Gloucester, a three-part storytelling series partly funded by Awesome Gloucester and hosted by Down the Fort: A Documentary and Archive Project.

Through her research, Mia learned that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Proclamation No. 2527 branded her Sicilian grandfathers, Filippo Millefoglie and Pietro Favazza, as "enemy aliens." What's more, Roosevelt's Executive Order 8970 established several Defensive Sea Areas off the coasts of the continental U.S., including areas in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and California. Fishermen found themselves barred from key fishing zones and coastal ports, designated as restricted areas for national security. Fishermen who were declared enemy aliens were barred from fishing and banned from the waterfront.

The federal government also requisitioned (or, in some cases, confiscated) fishing boats, either retrofitting them for military use or prohibiting their operation entirely. These restrictions effectively stripped many Italian immigrant fishermen of their livelihoods. Curfews and other limitations made it even more difficult for families to find alternative employment, exacerbating their financial hardships.

Mia shared more about her project, its inspiration and goals, the challenges she has faced, and the community response.

What inspired Branded as "Enemy Aliens"?

Both of my grandfathers were branded enemy aliens during World War II. They were Sicilian immigrant fishermen who were caught in the political turmoil. Having no knowledge of this proclamation, I never asked about their experiences. One day, I remember telling my grandfather Filippo that I was going out to California. His eyes twinkled, and he said, "Ah, California, I want you to go to San Francisco."

He named the street and said, "I used to have a fruit cart, and I used to shine the apples for pretty ladies."

I was in my twenties then, and just thought, "OK. My grandfather liked pretty ladies," and I dismissed it.

Later, I tracked the impact of the Proclamation and realized that after he couldn't fish in Gloucester, he went to California, where he sold fruit from a vendor's cart. So there was your pretty lady story.

I started piecing things together. The mystery of what my grandfathers did was intriguing to me. How did they make a living when they were banned from the waterfront? And they were banned from travel.

I haven't figured out how my grandfather arrived in California yet, nor how he managed to find work. But he managed, and during that time, my family, including their children, my father, my mother, and the grandmothers, were in Sicily during World War II. So the families were separated, straddling two homelands.

It was really tough to survive. They had been barely surviving on fishermen's salaries, and now couldn't send money over to Sicily. So, it was a personal connection, and exploring just how they survived made me realize their resilience.

Jennie & Lucia in Harbor Cove, Gloucester, MA, 1937. The fishing boat was requisitioned during World War II.

Photograph by John C. Adams. Courtesy of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA.

Describe the project.

This will be a three-part series. I have just completed part two, and we'll be working on part three. The work involves interviewing family members who have recollections of family stories of World War II in Gloucester, researching archives, and collecting photographs.

I hope to illuminate the impact of the Enemy Aliens Act on the families of fishermen in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and in Terrasini, Sicily. Today, I'm interviewing the grandchildren, who share their memories of their grandparents. Time is of the essence because there aren't many of those people left. I'm delving deeply into these family histories.

What am I trying to illuminate? One, it's very timely today. There are lessons to be learned when we apply these types of restrictions, if you will, on a selected group of people. Today, the words "Enemy Alien" have been resurrected in our administration as part of our national immigrant policy. Debates continue on due process and what constitutes a national risk.

During World War II, it is arguable whether there was due process or a registration process, but it was certainly a trying time. People were certainly interned, isolated, prosecuted, and unfairly restricted.

There was also loyalty and allegiance. Some of these immigrant families had children fighting in the service. So I'm also trying to shed light on what it was like for a mother who had one son labeled as an enemy alien, and another was serving the country. What conflicts did this cause among families? In essence, I want to capture the stories of conflict, loyalty, and allegiance in this relatively undiscovered history.

What challenges have you faced?

The challenge is really finding people who have recollections. And I feel an urgency to this work because I'm relying primarily on grandchildren. I actually do have two fishermen that I'm talking to who were closer to the source. Finding people who have experienced this period is the biggest challenge, along with navigating archives and records.

Through the U.S. Navy administration, I'm attempting to locate the list of all the boats that were requisitioned, their retrofitted details, and the dates and methods of their return. So that's a challenge. I have tracked down several boats, and their owners are featured in the stories.

In many ways, the vessels become characters. In families of fishermen, the boat is a loved family member.

I'm also investigating what happened in the harbors. We had U-boats in the harbor, and I just learned from family members that U-boats destroyed two fishing boats in Gloucester.

Have you encountered any surprises or particularly moving discoveries?

I was surprised and relieved to learn that the U-boats that destroyed the two Gloucester fishing boats out at sea allowed the men to get on dories.

Perhaps, the U-boat captains believed they had issued a death sentence, underestimating the strength of these men. They were out at fishing grounds, and their livelihood was destroyed. And then they were at the mercy of the sea in a dory, where they rowed to safety all the way to Maine. The men rowed for 36 hours in an attempt to survive and find shelter.

I'm thinking, "Look at the resilience and the courage of some of these people." I found that to be truly moving.

I am reading excerpts from newspapers about the role of women. They supported the war through fundraisers, purchasing Navy bonds, and forming societies for peace. These stories genuinely touch me.

What has been the response thus far?

The first response was, "Oh my goodness, Alien Enemies Act. That's exactly what is happening today."

When I wrote the first series, the Enemy Alien Act was not in our vocabulary. Then, the news brings out instances of searches, detention, and deportation of illegal immigrants. We begin learning about this Act, which had previously been used by presidents only in times of war. For this series, I don't intend to enter into the political arena, but I felt it necessary to acknowledge the Act for our readers.

I have particularly enjoyed readers sending me photographs of fishing boats, family members, wedding photographs, and more! It felt as if they were going through their family archives, saying, "Oh, this was my grandmother and grandfather during the war. And here they lived in the fort, and here they were restricted." They were delving back into their own family histories and archives, sharing little snippets. I loved all of this.

I think it's awakened people. We're trying to say, "Listen, this is important history. We're trying to let you know what your stories are; send us pictures, etc."

There has been a positive response. It's been just gratifying for me to hear people come forward. That's been great.

Looking back, I'm more in awe of my family and all the immigrants who came to this country as I explore this history, and this is just another piece that builds on it. It is an incredible story of resilience, isn't it?

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!